Dick Sheppard: Conscience of His Age

This article was originally published on the Consequence Forum.

On a misty September day in 1914, King George the Fifth, dressed in shooting gear, stands in a field at Windsor Home Park. He aims his hammer gun at a target several hundred feet away, and fires. Beside him, a dapper man in his thirties named Dick Sheppard covers his ears, winces and coughs from the acrid smell of cordite.

The King shouts, “Bull’s eye!” Dick looks impressed, but the King turns to him and scowls. “What’s this I hear about you intending to go to the front?”

Dick’s eyes twinkle. “Not to affront, you that is. Just behind the front. With Lady Dudley’s Base Hospital.” Although nearly as short as the King (at 5’6”), and slight, Dick radiates energy through his large-featured, expressive face.

The King waves his gun around wildly. “I don’t care if it’s with the Ladies’ Auxiliary, I simply cannot allow you to go.”

“With respect, Sir, I am needed.”

“I need you more right here.” The King swings his gun up to shoot and nearly strikes Dick, who ducks. The King fires and misses the target.

“Bugger!” The King looks disdainfully at the gun and thrusts it at Dick, who takes and sets it on a nearby stand. He picks up another gun and hands it to His Majesty.

“Surely you would agree that I have a patriotic duty – ”

“All very well to be patriotic, but in your condition? No, I am dead against it.”

“I do have a duty to a power even higher than yours.”

“Damn and blast, man. I am His representative, and I say no!”

“I will be sure to write – and say prayers for you.”

The King snorts and again waves his gun wildly, nearly pointing it at Dick, who squirms and moves awkwardly out of the way. “Prayers? I will be the one saying prayers for you.”

“Well, I would be very grateful for that.”

“And you should be grateful for the extraordinary preferment which has come to you.”

Dick flushes. “I am, but – ”

“But nothing. I will hear no more of it!”

Dick covers his ears as the King in a fury fires again and misses. Dick, looking grim and realizing that his audience is over retreats, limping. As his jacket flaps open we see that he wears a dog collar.

The King is so annoyed that, seeing a flock of geese he randomly shoots one and wings it. As the bird screeches and plummets, the King squints around, but Dick has disappeared into the mist. “Bloody young fool!” Scowling, he looks towards Windsor Castle.

A few weeks later, in a trench in France, shells burst and shrapnel and mud fly through the air. A unit of seven men huddles together against the elements and the deafening sounds, Dick Sheppard in the middle. Dressed in officer’s uniform with Chaplain’s cap badge, Dick has his eyes closed, his arms around the nearest soldiers.

“Amen.” He opens his eyes and squeezes the soldiers’ arms.

One soldier thrusts out a pistol for Dick to take. He shakes his head and pushes the weapon back to its owner, who frowns and says, “You’re mad!”

“That’s as may be.” To all the men he adds, “Godspeed men. It won’t be – ”

A whistle blows and the men scramble up the muddy trench, rifles in hand, Dick with them. He charges forward, wheezing and sweating, gripping a cross. Bullets whiz past and one soldier gets hit. Dick hobbles to the man, drops down, and cradles him as he staunches his wound.

*

These scenes depict how I imagine then-Vicar Dick Sheppard dealt with the King’s displeasure at Dick’s decision to serve in World War One as Chaplain [1] and his bravery in going over the top unarmed to minister to his men. [2] (A)

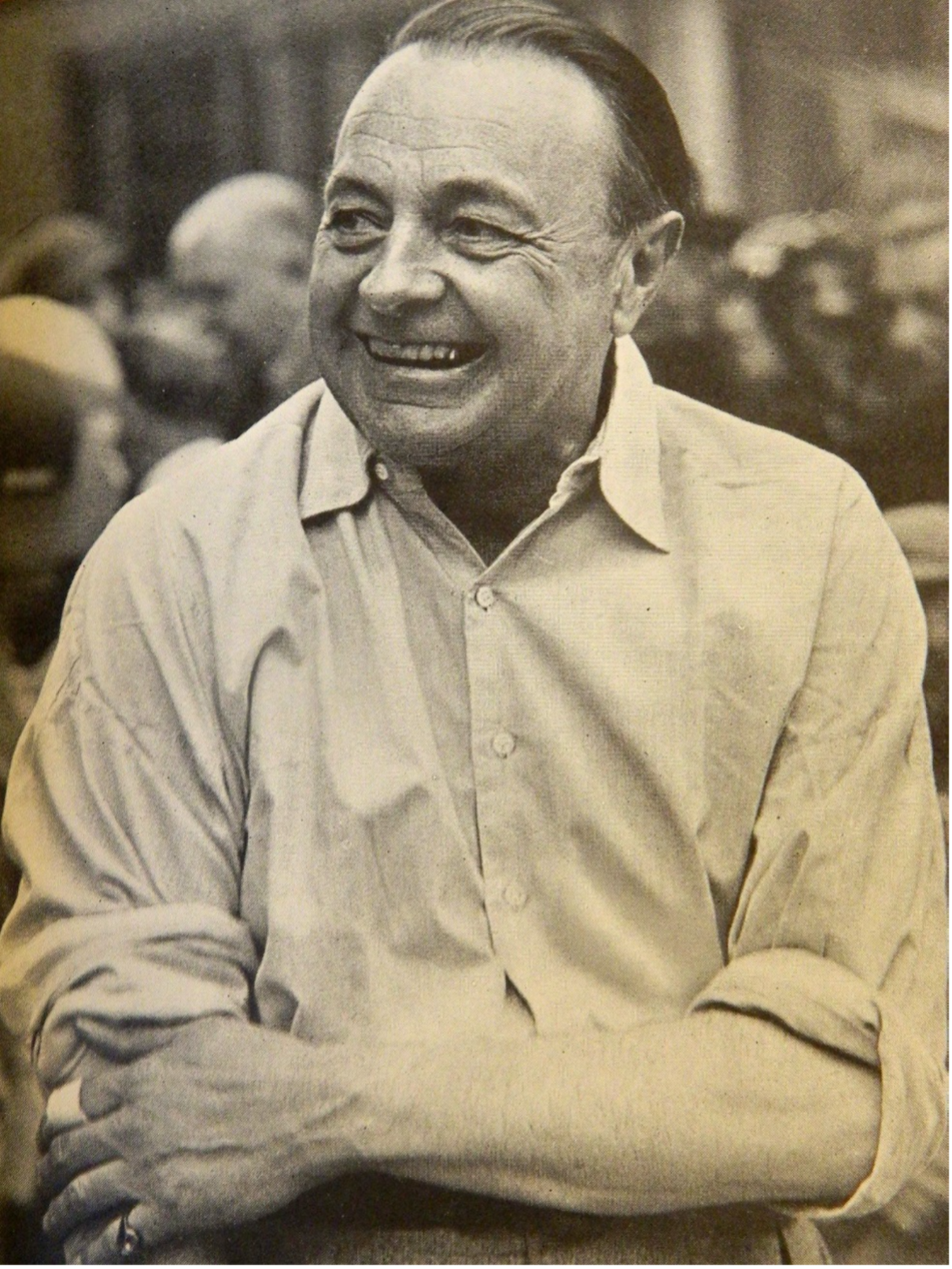

Dick Sheppard survived two months of war, but was invalided out, suffering exhaustion and shell shock. [3] Who was this reckless man who not only risked his position and the affection of the King of England by defying him, but also repeatedly risked his life by going into battle with his men, unarmed? The answer is not obvious, since H.R.L. Sheppard, known popularly as Dick, was a complicated personality by all accounts. Impish and charismatic, he lived life full throttle and daily practiced his ideal of love, but his energy and vision were counterpointed by bouts of self-doubt and depression throughout his life.

*

Born into privilege in 1880 – his father was a Minor Canon at Windsor Castle chapel – he grew up knowing Queen Victoria, whom his parents did not like, and with the family legend that he was descended from Napoleon. [4] Despite this, his childhood was unhappy and full of fear. His grandfather was a stern, selfish figure, who delighted in terrifying Dick, and when he was sent to Marlborough College he encountered another bully, the schoolmaster. Dick claimed that both of these men contributed to his inferiority complex. [5] He suffered from asthma and hated this boarding school so much that he deliberately drenched his bedsheets to get sick, a successful maneuver that got him sent home – permanently. [6]

After that rebellion (and one or two others, such as escaping to South America as a twenty-year-old and winning a tango competition in Buenos Aires), [7] he eventually went up to Cambridge University where he drifted along without a sense of vocation. [8] On graduating, he wound up working in the impoverished East End of London at a boy’s club. From there he made the huge leap to the fashionable West End as a curate. He was ordained as a Church of England priest, then suffered a breakdown in 1910, but by 1914 he had taken up the position of Vicar at St. Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square, interrupted only by his months at the warfront.

The famous church was in a derelict state and had all but lost its congregation. During his time there he transformed St. Martin’s in every way. It became a haven for everyone from soldiers, down-and-outs, to city messenger boys, the crypt kept open for soldiers to stay in while waiting for trains during the war [9] (and St. Martin’s strong social mission continues to this day). He performed when he preached, packing out St. Martin’s, yet seeming to address each individual directly. One of his parishioners was the King, and Dick became his Chaplain, [10] though he liked to joke that he was the King’s Charlie Chaplin who managed to keep him laughing even when His Majesty disagreed with his wayward chaplain’s views. [11] Despite this, Dick continued to be plagued by breakdowns, ill health, self-doubt, and periods of dejection. [12] He constantly overextended himself by helping whomever came into his path. On one occasion on the spur of the moment he accompanied a girl, adrift in London and estranged from her parents, back to her home in the north of England by train and then returned overnight. [13] Following the war, he developed a publication called the St. Martin’s Review and enticed many famous writers to contribute to it, including Thomas Hardy, George Bernard Shaw, Beatrice Webb, Arnold Bennett, and P.G. Wodehouse (of Jeeves and Wooster fame). [14] He also was the first priest to take to the air waves, on January 6th, 1924, using that brand-new technology, the radio, to preach, and he became known nationally as the wireless parson. [15] (B)

During his twelve years at St. Martin’s, not only did Dick’s popularity soar, but he received official recognition, including becoming a Member of the Order of Companions of Honour and being granted an honorary Doctor of Divinity by Glasgow University. [16] In 1929 he was made Dean of Canterbury Cathedral and then in 1934 a Canon at St. Paul’s Cathedral. [17] Despite these achievements, he was haunted by the war and the devastation caused even in those who had survived it, including his brother Major Edgar Sheppard, who suffered from shrapnel wounds. [18]

Dick had attempted to sign up for the Boer War in 1901, but he had an accident en route to the recruitment office when the horse-drawn cab he was travelling in crashed and an axle shaft pierced his leg. Ironically, the accident was probably a life-saver, although it left him with a permanent limp. [19] Throughout the 1920s and into the 30s, Dick became increasingly anxious about the possibility of war and vocal about opposing all war.

I want to focus on the final three years (from age 54 to 57) of his short life when he risked everything against all odds for his conviction. In 1934 Dick carried out a simple act, but one that would change his life and that of thousands of his countrymen. He wrote a letter to various British newspapers (not printed by The Times) asking people to sign and send the following pledge to him by postcard: “I renounce war and never again, directly or indirectly, will I sanction or support another.” [20]

Since he had to be out of the country, he asked his fellow pacifist ex-Brigadier-General Frank Crozier to receive the cards, but for the first two days nothing arrived and Crozier was distressed. On the third day a post office van arrived with bags full of postcards. [21] In the first few months, tens of thousands of them piled up in Dick’s office. Dick’s impassioned initiative was the first social justice campaign to use the mass, social media of the time – newspapers and postcards – in order to achieve its aim. Social media campaigns by Avaaz and others are commonplace today, but in 1934 this was something radically new.

Originally called Dick Sheppard’s Peace Pledge, the movement quickly organized and became the Peace Pledge Union (or P.P.U.). (C) Dick led mass rallies at the Royal Albert Hall in 1935 where famous writers and politicians such as Siegfried Sassoon and Aldous Huxley spoke out against war to a mostly youthful audience, peppered with veterans of the First World War. [22]

In addition to his duties as newly-appointed Canon at St. Paul’s, the pacifist parson travelled the country, to the detriment of his health at times, giving talks and encouraging pacifist groups to form. On more than one occasion he delivered a rousing speech and then collapsed from an asthma attack afterwards. He wrote his most popular book in 1935 called We Say “No,” in which he articulated his absolute pacifism, in other words his belief that if you accept the brotherhood of mankind, then it follows that war is murder and all war is civil war. Dick persuaded many people that pacifism was not a romantic fantasy, but that those enthralled by the glory of war were the romanticists. [23] In some cases he changed their views forever.

Aldous Huxley, the cynical, cutting-edge modernist writer, not only sent in his postcard pledge, but his subsequent discussions with Dick convinced this atheist that pacifism needed spiritual force behind it to be effective. [24] After publishing Brave New World in 1932 and starting on an autobiographical novel, Huxley had become so anxious about the possibility of another war that he suffered from writer’s block. (D)

His deep connection with Dick Sheppard helped inspire him to complete his most profound novel, Eyeless in Gaza (1936), which includes a fictionalized Sheppard, and to write articles and an Encyclopaedia of Pacifism (1937), presenting reasoned arguments against war. Huxley’s involvement in the pacifist movement turned him firmly on the path towards mysticism, which he travelled for the rest of his life. [25]

Antiwar publications flowed into the mainstream by many other writers as diverse as A. A. Milne (of Winnie the Pooh fame; Peace With Honour 1934), the prolific popular writer Beverly Nichols, now remembered for his gardening books (Cry Havoc! 1933), and the distinguished philosopher Bertrand Russell (Which Way to Peace? 1936). Initially only men had been called to sign the peace pledge, being primarily responsible for war, but in 1936 women were invited to sign, and 50,000 did so. [26] Dick Sheppard also invited notable writers and politicians to become sponsors of the Union. Along with Huxley and Russell, the writers Siegfried Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, Vera Brittain (who wrote the most famous memoir of the First World War, Testament of Youth), Rose Macaulay, Lawrence Housman, Storm Jameson, John Middleton Murry, Max Plowman, Clive Bell, the House of Lords Labour leader Lord Ponsonby, the Labour Party leader George Lansbury, and others became signatories. Nevertheless, the majority of P.P.U. members were the poor, traditionally the fodder for war. [27]

One of Dick’s most famous (or infamous depending on your point of view) actions was to write a letter to Hitler (also sent to and published in The Times) in 1936, imploring him to allow Sheppard to enter Germany to preach peace. He never received a reply. [28] This genuine attempt at reconciliation might seem reckless, or even absurd in retrospect, but you have to remember that people in 1937 were just like many of us today, anxious about the threat of war as we observe leaders come into power and take alarmingly aggressive stances towards each other. We want to do something to stem this war mongering. Dick Sheppard did. His action provoked attacks in the press, including a David Low cartoon showing Dick and Aldous Huxley on the left of the image, arms outstretched, with Hitler and Mussolini on the right holding massive handkerchiefs and weeping in response to the peace offering. Opposition to the Peace Pledge Union increased through the later 1930s. The organization was accused of treachery and sedition, and of being pro-Nazi. [29] Detectives spied on Peace Pledge members. [30] Dick was forbidden to preach peace on the radio. [31] Dissension within the ranks also broke out over such issues as the limits of pacifism, and Dick ironically had to fight to keep peace at the Peace Pledge Union. [32] On the home front, his wife Alison, frustrated by his invalidism and perceived neglect of her, had an affair and then left him for the novelist Archie Macdonell.[33] Dick was devastated, blaming himself, and believed that he could no longer preach peace or love, having lost his. [34]

Despite it all, Dick continued to throw himself into his cause, whether it was carrying a sandwich board, advertising a mass protest against war, up and down the Strand in miserable February weather, or leading a peace meeting of 15,000 people in a field near Dorchester during a June heatwave.

At the latter, Vera Brittain was so impressed with this man of genius, as she called Sheppard, and his love-based pacifist message that she jettisoned her speech on collective security, and later viewed the event as a turning point in her life. [35] (She remained an ardent active pacifist for the rest of her days). At a camp at Swanick in August 1937, Dick made the pacifist meetings fun and memorable by organizing games, playing tricks, and acting – apparently he was a great mimic. [36] After a speech there he suffered a severe attack of asthma. A friend fetched his breathing machine (German-made, as Dick relished conveying) along with a dark bottle of fluid. Dick quickly had the friend in stitches when he laughed uproariously and told her that his hair wash probably wouldn’t aid the cause. [37]

Later that August he retreated briefly from his relentless crusade for peace and travelled to Chartres in France, where he walked the labyrinth, his head bowed, hands clasped, gripping a cross hanging from his neck. [38] On his return, he struggled with a momentous decision for nearly a month. Despite being the most popular parson in the country, he felt it was also one of the loneliest things in the world. [39] Then, on the 18th of September, he finally resigned from St. Paul’s, believing it was a scandal to its namesake and had failed to live out the love of Christ in addressing social problems, including the threat of war. When asked what was next, he said that he intended to take his little show (as he liked to call his peace platform) on the road, pelting people with the P.P.U. message. [40]

Perhaps his greatest moment came soon after when he was nominated by students as the pacifist candidate for Rector of the University of Glasgow. Opposing him would be two prominent professors, William Macneile Dixon and J.B.S. Haldane, and most notoriously Winston Churchill, who supported rearmament. [41] Dick firmly believed that he hadn’t a sliver of a chance, but it was out of his hands since the rules strangely forbade campaigning by the candidates themselves. Instead, rowdy Scottish students organized rallies with slogans on posters, such as “Sheppard the Flock for Peace,” and chanting. Ironically, in the case of the pacifists, the factions pelted each other with dough bombs, made up of sawdust, motor oil, and even porridge (how very Scottish!). [42] The battle captured the attention of the national media, [43] and when Dick unexpectedly won by a large majority it seemed as if pacifism was a force to be reckoned with in the United Kingdom. Dick was overwhelmed by congratulatory calls, letters and telegrams from all quarters. Bertrand Russell wrote that he was overjoyed. Glaswegian George MacLeod, Baron MacLeod of Fuinary, quipped that Sheppard should apply to Rome for immediate canonisation, ironic given that he had just resigned as a Canon.[44] Sheppard believed that the victory was the verdict of youth on his cause. [45] By this time there were 715 local pacifist Peace Pledge Union groups spread throughout the country, with a membership of 118,000. [46]

Just over a week later, on October 31st, he returned home late at night, walked past some letters and messages on his hall table, including one from his wife Alison asking to return to him, and entered his study. [47] He staggered to his desk breathing heavily, another asthma attack imminent, but his heart gave way and he slumped over. [48] Dick had sacrificed everything for peace. Just three days before he died, however, he said that it would take his death to bring pacifism fully to life. [49] On All Soul’s Day (Nov. 2nd) his body was returned to St. Martin’s, where he lay in state watched over by members of the Peace Pledge Union as one hundred thousand people from every walk of life, including street people, prostitutes, ex-soldiers, politicians, and members of the aristocracy filed past to pay their respects to their friend and inspiration. [50] He received a state funeral, flags at half-mast, broadcast on the B.B.C. and filmed as a newsreel.

His funeral procession wound its way from St. Martin’s to St. Paul’s with tens of thousands lining the streets, and then his body was laid to rest at Canterbury Cathedral. The outpouring of grief was extraordinary, perhaps only comparable in recent times to that following Princess Diana’s death. All across the United Kingdom, people wrote tributes in newspapers, held church services and meetings in his honor, and published books of commentary and reminiscences. Although thousands pledged to carry on the peace parson’s work, the anguish arose partly from an awareness that not only had Britain had lost an exceptional human being, the conscience of the nation as he was known, but also the battle for peace. [51]

The Peace Pledge Union did carry on, despite increasing persecution. The police threatened peace pledge printers and publishers with imprisonment for publishing any “propaganda” opposing the war effort. Open air speakers preaching peace, P.P.U. members carrying posters such as “War Will Cease When Men Refuse to Fight. What Are YOU Going to Do About It,” and Peace News sellers were arrested. [52]

As everyone knows, the P.P.U. was not able to prevent Britain from entering the war. This has been seen as a failure and has led to the eclipse of the movement in history, but the reality is more complex since the Union intensified its efforts after war was declared. It forced attention onto human rights and humanitarian goals. P.P.U. members sponsored Jewish refugees from Germany when the British government closed its door, and campaigned for food relief to starving people in Europe, including Germany, as well as helping German prisoners of war. [53] Some of its members kept opposition to night-bombing an issue in the press. [54] The Union provided a community of resistance and managed to keep Peace News in circulation to 30,000 subscribers. [55] It gave hope to people during the darkest days of the war. Perhaps most importantly, as Cecelia Lynch details, the Peace Pledge Union helped lay the groundwork and establish the norms of international behavior, such as a broader sharing of power among nations, norms that were put into place in the United Nations after the war. [56]

By 1945 the Union still had over 98,000 active members. [57] Their non-violent resistance demonstrations at Alderston anticipated the yearly march, and many P.P.U. members joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, initiated by another Canon of St. Paul’s in 1957. [58] The Peace Pledge Union still actively advocates against war today, its headquarters in a modest building set back off York Way on Peace Passage in Camden Town, London (see http://www.ppu.org.uk/). According to historian of pacifism Martin Ceadel, the Peace Pledge Union was the strongest pacifist movement in history. [59]

This is quite a legacy for that unconventional, mercurial, “irresistible” [60] preacher with an outrageous sense of humor, a knack for drama, and a huge heart. His mantra – not peace at any price, but love at all costs [61] – resonates even more powerfully today: would there were more like him in the current climate of violence and upheaval. Like the patron saint of the church he loved, St. Martin, he was a soldier turned priest, but unlike St. Martin he continued to soldier on for peace, at great risk to his reputation, standing in the Church, marriage, health, and, ultimately, his life.

Why does he remain an unknown soldier today? Despite the fact that there were a few earlier biographies, including R. Ellis Roberts’s, H.R.L. Sheppard Life and Letters (1942), Sybil Morrison’s I Renounce War. The Story of the Peace Pledge Union (1962), and Carolyn Scott’s Dick Sheppard (1977), on which I have drawn, along with his papers in the Lambeth Palace Library and the Bodleian Library at Oxford, there has been nothing substantial written on his life in the last forty years. I suspect that the reasons are complex, but among them must be that his movement did not achieve its immediate aim, the prevention of war against the Nazis, whose extreme aggression and cruelty seemed by 1939 to leave no alternative to war. As well, his approach to pacifism flowed from his Christianity, and there was never agreement as to whether Christians should participate in war during his time, nor up to the present. We live in an era when positive, faith-inspired stories remain under the radar, and those involving religious leaders in particular are ignored or at best treated with skepticism.

Even so, while Dick Sheppard may be unknown to most, he is not completely forgotten 83 years after his death in 1937. When I spoke with the Associate Vicar of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Katherine Hedderly, she told me that Dick was well-remembered by her congregation. [62] Every year parishioners go on a four-day spring pilgrimage from their London parish to Canterbury Cathedral to raise money for the homeless, in memory of Dick Sheppard, the shepherd of his flock for peace. [63]

Footnotes

(A) The process of writing this article was rather unusual, since I have based it on my award-winning (and as yet unproduced) screenplay Peace Pledge, especially the opening scenes. I faced several challenges in transforming the story of the British peace movement for the screen. For one thing, no one has heard of this story, but they know that WWII happened, and the peace story complicates the dominant narrative that WWII was an inevitable and just war. With 60 million killed, can it in any way be considered a successful war? Another challenge was to avoid back-projecting the outcome or attitudes towards absolute pacifism, but to recreate the anxiety of people in the 1930s, who of course did not know that war would happen and for over 136,000 of whom absolute pacifism was viable. Perhaps the main challenge was to avoid being didactic while showing that pacifism is neither dull nor passive, but that it hinges on concentrated, continuous, disciplined activism. This meant dramatizing some scenes, such as the King’s opposition to Dick’s participating in the First World War, which was real, but which Sheppard’s father conveyed to him in a letter – not nearly as dramatic as the scene opening this article and my script. My principle has been to capture the essential truth of historical events, without adhering slavishly to details. Although Peace Pledge depicts clashes between pacifists, fascists, and the police, the goal was to convey the trauma of fighting and war without glorifying it, as I would argue happened in Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge. That film portrayed a long and extremely graphic segment of war violence, which relies on the tropes of heroism. The enemy was objectified, their stories and suffering never shown. Peace Pledge counters this by confining war scenes to relatively brief flashbacks; by giving a voice, rationale and humanity to those opposed to pacifism; and by showing the greater effectiveness of collaboration over conflict, as in passive resistance. Other aesthetic challenges included choice of protagonist; my original impulse was to make either Dick Sheppard or Aldous Huxley the protagonist, but in the end I decided on a fictional “everyman” as the viewpoint character, an unemployed and embittered First World War vet, one of the poor who had been made the fodder of war. Thematic decisions included developing a love plot as a counter to the violence depicted. Film has an advantage because it can take the long view, and I decided to include a coda to Peace Pledge, flashing forward to show the now elderly protagonist with his children campaigning for nuclear disarmament in the late 1950s. The struggle is lifelong but must be taken up by the next generation. Peace Pledge is about standing up for what you believe in, even against all the odds, and deals with redemption, love and the power of the human spirit. It won the Wildsound Festival in Toronto, and here is a table read of an earlier version of the script below.

—George M. Johnson

[1] Roberts includes a letter from Dr. Edgar Sheppard, Dick’s father, to Dick detailing the King’s immense displeasure at Dick’s decision to go to war. 83.

[2] Royden “Peacemaker” 76.

[3] Roberts, 84-5.

[4] Roberts, 6; Scott Sheppard 16-18.

[5] Roberts, 9-10; 14, Sheppard quoted in Roberts 16.

[6] Roberts 18.

[7] Roberts 24.

[8] Roberts 25.

[9] Paxton 16; Roberts 93, 102; Scott 80-82.

[10] Roberts 128.

[11] Dick’s friend Laurence Housman alludes to the moniker in a letter quoted by Scott 208. Vera Brittain’s husband George Catlin noted that Sheppard reminded him of Charlie Chaplin. Brittain Chronicle 306.

Ironically, Dick was a friend of Charlie Chaplin’s and encouraged him in We Say “No” to make a pacifist film showing “the little man, bewildered and afraid, caught up in the dreadful machinery of war” 159. I do not know whether this had an influence on Chaplin’s making of The Great Dictator in 1940.

[12] Roberts 95-6.

[13] Roberts 106.

[14] Roberts 107-8.

[15] Roberts 111-113; Glasgow Herald Mon. Oct. 25, 1937, 12.

(B) Upon reading this piece for the first time, I was struck by the amount of empathy I held for Dick Sheppard. Of course, being born into privilege over a century ago would appear much different than what we understand “privileged” to mean today, yet the essence of Dick’s biography is one I believe many members of present-day society can relate to; a person who does everything in their power to make the world a better place. Dick Sheppard overcame grade-school bullies, he experienced the debilitating effects of mental illness, and even amidst the tragic realities exposed by what must have felt like never-ending conflict, he persisted in advocating for what he believed to be in the best interest of humanity.

—Consequence Asst. Nonfiction Editor Lyida Tinsley

[16] Roberts 165, 19.

[17] Roberts 190, 242.

[18] Roberts 137.

[19] Ellis 24.

[20] Morrison 8.

[21] Morrison 8-9.

[22] Morrison 10, Bedford 311.

(C) It can be said that the spark that started the Peace Pledge Union was a sermon delivered by Harry Emerson Fosdick of New York City, who preached on Armistice Sunday of 1933 about rejecting war “for its consequences, the lies it lives on and propagates, for the undying hatred it arouses, for the dictatorships it puts in the place of democracy” (qtd. in Sybil Morrison’s I Renounce War: The Story of the Peace Pledge Union, page 8). This sermon inspired Dick Sheppard to write his original letter in 1934 asking for readers to sign and send the pledge to him via postcard. Fosdick was an inter-denominational American Christian pastor who spent much of his life ministering in New York City. A liberal preacher who supported evolutionism and explicitly stated his opposition to racism and other injustices, Fosdick was also a major influence on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

—Consequence Nonfiction Editor C.H. Gorrie

[23] Sheppard, We Say “No” 57 ff.; Roberts 271.

[24] Huxley 100, 000 Say No 5.

[25] See Johnson, “Misty-Schism.”

(D) I first read about Dick Sheppard in Sybille Bedford’s two-volume biography of Aldous Huxley, while working on him for my book Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond: Grappling With Ghosts (Palgrave, 2015). I wondered what sort of man this Anglican priest was who had convinced Huxley not only to take up pacifism but to recognize that it required a spiritual dimension to succeed. I soon realized that Sheppard and his Peace Pledge Union had been reduced to a footnote by literary historians of the period, such as Valentine Cunningham, who wrote in British Writers of the Thirties that the Peace Pledge Union was “really such a non-starter among ’30s intellectuals” (69). This was clearly inaccurate, although it was easy to dismiss the peace movement in retrospect since it did not achieve its immediate aim of keeping Britain out of war. I discovered a huge number of books and articles about peace in the 1930s and Dick Sheppard in particular, and realized what a significant figure, a key figure he had been. The dominant Churchillian narrative had obscured this counter-narrative, which I determined to restore for the widest audience possible and that is why I chose to write a film script.

—George M. Johnson

[26] Morrison 17-18.

[27] Huxley notes this in both Ends 184 and Eyeless 523.

[28] Roberts 283.

[29] Morrison 38, 32.

[30] Morrison 41.

[31] Roberts 276.

[32] Roberts 296.

[33] Scott 232.

[34] Roberts 328-9.

[35] Brittain Testament of Experience 164-5.

[36] Roberts 305.

[37] Anonymous Sheppard 53.

[38] Roberts 306.

[39] Roberts 329.

[40] Roberts 306.

[41] Morrison 24.

[42] Glasgow Herald Mon. Oct. 25,1937, 12.

[43] Times (London), Monday, October 25, 1937, 11.

[44] Scott 239.

[45} Roberts 309; Morrison 26; Scott 239.

[46] Ceadel Semi-Detached 360, 334.

[47] Roberts 333.

[48] Roberts 311; Scott 243.

[49] Anonymous Sheppard 30.

[50] Roberts 312; Scott 245.

[51] Roydon “Peacemaker” 80.

[52] Morrison 51.

[53] Morrison 33-4; 58-59.

[54] Morrison 59.

[55] Morrison 54.

[56] Lynch 123.

[57] Morrison 62.

[58] Morrison 78, 91.

[59] Ceadel Semi-Detached 334.

[60] So called by caricaturist Max Beerbohm, who added: “I have never heard of anybody who didn’t find him so.” As cited in Roberts 200.

[61] As cited in Brittain, Testament of Experience 173.

[62] There is a Dick Sheppard chapel at St. Martin-in-the-Fields.

[63] This pilgrimage has apparently been suspended because of the pandemic.

Bibliography

Anonymous. H.R.L. Sheppard. A Note in Appreciation. London: Cobden-Sanderson, 1937.

Bedford, Sybille. Aldous Huxley. A Biography. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus, 1973-74.

Brittain, Vera. Chronicle of Friendship. Vera Brittain’s Diary of the Thirties 1932-1939. Ed.

Alan Bishop. London: Victor Gollancz, 1986.

—. Testament of a Peace Lover. Letters From Vera Brittain. Ed. Winifred and Alan Eden-Green. London: Virago, 1988.

—. Testament of Experience. London: Gollancz, 1957.

—. Testament of Youth. London: Gollancz, 1933.

Ceadel, Martin. Semi-Detached Idealists. The British Peace Movement and International Relations, 1854-1956. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. 1932. London: Flamingo, 1998.

—. An Encyclopedia of Pacifism. London: Chatto and Windus, 1937.

—. Ends and Means. London: Chatto and Windus, 1937.

—. Eyeless in Gaza. 1936. London: Chatto and Windus, 1955.

Johnson, George M. “Misty-Schism”: The Psychological Roots of Aldous Huxley’s Mystical Modernism.” In Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond: Grappling With Ghosts. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Lynch, Cecelia. Beyond Appeasement: Interpreting Interwar Peace Movements in World Politics. Cornell University Press, 1999.

Milne, A. A. Peace With Honour. An Enquiry into the War Convention. London: Methuen, 1934.

Morrison, Sybil. I Renounce War. The Story of the Peace Pledge Union. London: Sheppard Press, 1962.

Nichols, Beverly. Cry Havoc! Toronto: Doubleday Doran and Gundy, 1933.

100,000 Say No! Aldous Huxley and ‘Dick’ Sheppard Talk About Pacifism. London: The Peace Pledge Union. nd.

Paxton, William, Philip Inman et. al. Dick Sheppard. An Apostle of Brotherhood. London: Chapman and Hall, 1938.

Royden, A. Maude, “The Peacemaker,” in William Paxton, Philip Inman et. al. Dick Sheppard. An Apostle of Brotherhood. London: Chapman and Hall, 1938.

Roberts, R. Ellis. H.R.L. Sheppard. Life and Letters. London: John Murray, 1942.

Russell, Bertrand. Which Way to Peace? London: Michael Joseph, 1936.

Sheppard, H.R.L. We Say “No.” London” John Murray, 1935.

Scott, Carolyn. Dick Sheppard. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1977.